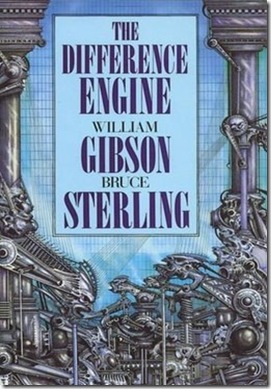

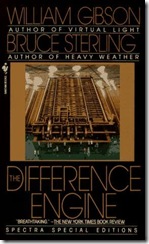

This is the first publication of a first draft of an article I wrote in late 1990 for some magazine or other, at the time of the publication, by Gollancz in the UK, of the hardback edition of 'The Difference Engine', a joint work by Gibson and Sterling. I prefer it to the final edit.

This is the first publication of a first draft of an article I wrote in late 1990 for some magazine or other, at the time of the publication, by Gollancz in the UK, of the hardback edition of 'The Difference Engine', a joint work by Gibson and Sterling. I prefer it to the final edit.

VICTORIAN CYBERPUNK

'Imagine a Victorian London in which Charles Babbage's  brass and steam prototype computer has transformed society into a Dickensian form of 'Brazil', a polluted capital ruled over by savants. The Rads led by Lord Byron are in power whilst New York has been captured by a Marxist Commune. People this with secret agents and societies, post-Luddite anarchists, and you have some conception of the steam-heated world created by the imaginative fusion of leading cyberpunk writers William Gibson and Bruce Sterling in their tour de force novel 'The Difference Engine'.

brass and steam prototype computer has transformed society into a Dickensian form of 'Brazil', a polluted capital ruled over by savants. The Rads led by Lord Byron are in power whilst New York has been captured by a Marxist Commune. People this with secret agents and societies, post-Luddite anarchists, and you have some conception of the steam-heated world created by the imaginative fusion of leading cyberpunk writers William Gibson and Bruce Sterling in their tour de force novel 'The Difference Engine'.

As the self-styled 'Bill and Bruce show' roared through London, Manchester and Birmingham, your correspondent raced to keep pace, snatching time at a Groucho club reception, at their London publishers and at Andromeda in Birmingham, which Gibson dubs "a sf speciality shop with intense sub-culture vibes", to capture as much of their rich conversation as possible before they headed back to Vancouver and Austin respectively to channel their fearsome imaginations into yet more tense and fevered prose.

Science fiction has always been powered by adolescent intensity and to outsiders remains an arcane and tropical jungle of strange beasts, mutated sensibilities and private languages.

Cyberpunk blossomed from fertile soil: the left-liberal pole of American sf (Theodore Sturgeon/Fritz Leiber), the British New Wave (Ballard, Moorcock and Aldiss), William Burroughs and French underground comics to name just some of the key elements. Out of this grew a sensibility shared by a generation of writers and artists which was first labelled in an eponymous short story by Bruce Bethke and by the critical anthologist Gardner Dozois, the Italian editor of Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction magazine, in the early 80s.

Bill Gibson and Bruce Sterling are amongst the movement's leading lights and have complementary views on the terms meaning and value.

Gibson, expounding in his wry, rural Virginian accent that seems little affected affected by his long sojourn in Canada, sees it as a broad tendency in popular culture, citing his conversations with Ridley Scott over 'Blade Runner' as another example of the Zeitgeist.

Gibson, expounding in his wry, rural Virginian accent that seems little affected affected by his long sojourn in Canada, sees it as a broad tendency in popular culture, citing his conversations with Ridley Scott over 'Blade Runner' as another example of the Zeitgeist.

Whilst admitting to be initially quite unhappy with the label "because it was a label and because my experience with subcultures and bohemian trends is that once they have been labelled by the press they've had it." When pressed to define what he drily calls " a neologism that's rather long in the tooth" he refers back to C.P.Snow's classic analysis, claiming global media cyberpunks are scientist/artists, operating from the slash between the two cultures.

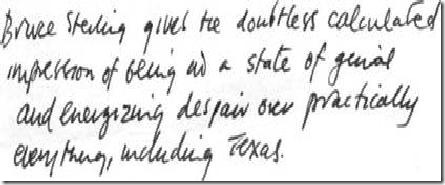

Sterling's yee-ha machine-gun delivery would defeat the nimblest of stenographers but in simple terms he opines that if one is to have a label, he'd much prefer to have just one.

nimblest of stenographers but in simple terms he opines that if one is to have a label, he'd much prefer to have just one.

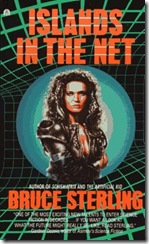

Aged 36, he's the author of highly prized short fiction and  four previous novels, Involution Ocean, The Artificial Kid, Schismatrix (1985) and Islands In The Net (1988).

four previous novels, Involution Ocean, The Artificial Kid, Schismatrix (1985) and Islands In The Net (1988).

Pre-cyberpunk his "knitting circle of revolutionaries" were branded under such assorted tags as "dark futurists", "outlaw technologists" and "punk-sf" to name just a few. To underline that things have now got well out of hand, he recalls his recent meeting with the Cyberpunk Front from Milan, a sub-Red Brigade group completed with a semiotic guru and identical jackets emblazoned with their emblem - a winged brain with lightning bolts.

His intro the seminal cyberpunk anthology 'Mirrorshades' describes their stance as 'the point where hacker and rocker overlap' which leads him into a long tirade against the New York Times categorisation of hackers as computer criminals.

This is dear to his heart and close to home as Austin has recently been the centre of a major bust - 'Operation Sun Devil* - by the US Secret Service, whose two main functions are to protect the President and prosecute counterfeiters. Their current aim is to set themselves up as the computer police and their recent raid on Steve Jackson Games, siezing all manuscript copies of a new game book entitled 'GURPS Cyberpunk', has set the stage for the first major civil liberties battle on the new electronic frontier.

The interconnections between what Sterling describes as "the high-level hackers and the old San Francisco underground, Tim Leary and the Virtual Reality people" has led to the establishment of the Electronic Frontier Foundation by Mitch Kapor (originator of the software Lotus 1,2,3), Steve Wozniak and John Perry Barlow ("the Grateful Dead lyricist whose in the net a lot") to mediate between the two sides. Such fascinating digressions are hard to ignore.

In retrospect Gibson, now in his early 40s, sees the organic progression that has led him through his short story collection (Burning Chrome) and the brilliant trilogy of novels (Neuromancer, Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive) and clearly defines his major obsessions and themes:

"The attempt to come to terms with being human in an information society; the real politics and economics of the media world; the obsessive pursuit of the trauma zone of new technology, the point where you are genuinely shocked and frightened; the focus at which the novel seems monstrous, like the moment the drawer first slides out of your CD machine; ecstasy and dread, the post-modern sublime1.

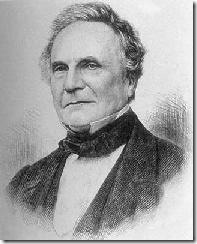

This Victorian novel span out of a bar-room fantasy about a world in which Babbage's engine has worked and developed through a reading of Babbage's "express political philosophy, which is both startlingly modern and sinister" and which heavily influenced Marx, one of his great admirers.

The contemporary nature of the period fascinates Gibson. "I don't think there's another time in history that we can look to to see so closely the same tremors and turmoil, the same feelings of wonder and dismay."

His readings of the tabloid journalism and pulp fiction of the period startled him. "It is full of extremely peculiar, hallucinogenic writing, wonderfully resonant, full of vertigo and nausea, as if their notions of time and space had been yanked out of alignment."

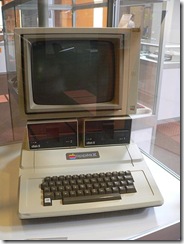

The collaboration between the the tall, rangy Gibson and  the short, intense and bespectacled Sterling, began in the early 80s and their joint novel was produced entirely by correspondence on obsolete Apple IIs, with discs being sent back and forth by FedEx couriers. "We agreed any given version would supercede the previous version," says Gibson " and that we could only ever go forward." He likens it to tunnelling with a lot of regrouting along the way.

the short, intense and bespectacled Sterling, began in the early 80s and their joint novel was produced entirely by correspondence on obsolete Apple IIs, with discs being sent back and forth by FedEx couriers. "We agreed any given version would supercede the previous version," says Gibson " and that we could only ever go forward." He likens it to tunnelling with a lot of regrouting along the way.

Gibson lived in the Victorian section of Toronto called The Annexe during the "high hippy days" whilst Sterling spent three years living in Madras, with its "phantom after-image of the Raj".

A self-styled research freak, who loves "pursuing minutiae ot no particular end", this book provided him with the opportunity of frolicking through the Humanities Research Centre at the University of Texas, which contains more than $60 million worth of literary manuscripts and ephemera including Edgar Allen Poe's writing desk. He tells me "Its installations are protected by argon gas. If fire breaks out you have 45 seconds to leave before its flooded with noble gases and your history."

Whilst in London they were taken to see the  reconstruction of Babbage's engine that the Science Musuem are building, using a combination of period manufacturing techniques and advanced computer-aided design. "We had to put on white gloves", says Sterling, " just like the 'clackers' (Victorian hackers) in our book." He was obviously delighted at life's imitation of art, what he terms a "genuine second-generation effect".

reconstruction of Babbage's engine that the Science Musuem are building, using a combination of period manufacturing techniques and advanced computer-aided design. "We had to put on white gloves", says Sterling, " just like the 'clackers' (Victorian hackers) in our book." He was obviously delighted at life's imitation of art, what he terms a "genuine second-generation effect".

By our third conversation, madness and throat exhaustion was taking over. Time only to learn that Gibson has written the first screenplay for 'Alien 3' ("your readers may not realise that 'Total Recall' went through 30 full screenplays"), that his script based on his own short story 'New Rose Hotel' is drifting around in Hollywood and that 'Burning Chrome' sits with Carolco with James Cameron slated to direct it after 'Terminator 2'. There were sounds of screeching in the background. We agreed to meet in Vancouver next year to celebrate Greenpeace's 20th anniversary. The line went silent except for the words 'ecstasy and dread' that kept ringing in my ears. '

scribbled underneath the typescript is the following note:

I first met Gibson and Sterling at the cramped upstairs publishers party at the Groucho Club in London's Soho.

Weirdly, one of the main characters in 'The Difference Engine' is geologist Gideon Mantell, one of the earliest dinosaur hunters, who with his wife discovered and identified the fossil remains of a creature they called iguanodon. He went on the conceptualise the idea of the 'Age of Reptiles' and can now be seen as the Godfather of Dinosaur Culture.

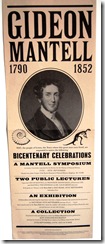

Weird because Gideon Mantell lived in my town, Lewes. His magnificent house still stands proud in the High Street, a double-fronted mansion with columns topped with Ammonites (and built, coincidentally or not) by a builder named Amon Wilds.

As chance would have it, there had just been a centenary  celebration of his life, bringing together academics from across the world, including Mantell's biographer Dennis R. Dean. A beautiful Victorian-style poster (above) was produced for the event and I arrived that night holding one, which I gave to Sterling and Gibson. Their jaws dropped.

celebration of his life, bringing together academics from across the world, including Mantell's biographer Dennis R. Dean. A beautiful Victorian-style poster (above) was produced for the event and I arrived that night holding one, which I gave to Sterling and Gibson. Their jaws dropped.

FOOTNOTES

- In 1992 Bruce Sterling's first nonfiction book was published: 'The Hacker Crackdown: Law And Disorder On The Electronic Frontier', a work of investigative journalism exploring issues in computer crime and civil liberties. Sterling released the entire text of the book on the Internet as non-commercial "literary freeware," and maintains a long term interest in electronic user rights and free expression.

- Steve Jackson Games v. Secret Service Case Archive: On March 1 1990, the offices of Steve Jackson Games, in Austin, Texas, were raided by the U.S. Secret Service as part of a nationwide investigation of data piracy. The initial news stories simply reported that the Secret Service had raided a suspected ring of hackers. Gradually, the true story emerged. More than three years later, a federal court awarded damages and attorneys' fees to the game company, ruling that the raid had been careless, illegal, and completely unjustified. Electronic civil-liberties advocates hailed the case as a landmark. It was the first step toward establishing that online speech IS speech, and entitled to Constitutional protection... and, specifically, that law-enforcement agents can't seize and hold a BBS with impunity. See: Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

- For some great examples of 'steampunk' see Metachronicles. On their entry on this book, Eric Orchard writes: 'The Difference Engine ...definitely changed the course of science fiction by popularizing the idea of an altered Victorian world. It ushered in the era of re-imagined pasts. The Difference Engine is considered by many to define the subgenre of Steampunk.'

- Gibson's Alien III filmscript is on the net

No comments:

Post a Comment